Introduction

Traditionally, drug-like chemical space was confined to the region defined by the well-known Lipinski ‘Rule-of-Five’ criteria: drug molecules typically had logP ≤ 5, MW ≤ 500, H-bond donor count ≤ 5, and H-bond acceptor count ≤ 10.1 Over the years, these boundaries have shifted significantly, giving rise to new therapeutic modalities that no longer fit within these criteria. As a result, a paradigm shift has occurred, leading researchers to explore the ‘Beyond Rule-of-Five’ (bRo5) drug space.2

A prime example of such new modalities are PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras).3 PROTACs are composite molecules designed to attenuate the function of specific proteins by binding to the target protein and inducing its degradation via the intracellular ubiquitin-proteasome system. Structurally, PROTACs are heterobifunctional molecules, consisting of two small molecular ligands connected by a covalent linker. One ligand recognizes the target protein, while the other recruits a ubiquitin E3 ligase to initiate the degradation pathway. Overall, this results in large molecules which clearly fall outside the traditional Rule-of-Five guidelines.

Predicting properties for bRo5 compounds is particularly challenging, as most existing models have been trained on experimental data from classic drugs, meaning large, complex molecules often fall outside their applicability domains. While ACD/Labs’ predictive algorithms continuously evolve to adapt the models to novel chemistry, available data for bRo5 compounds still represents only a relatively small fraction of the overall datasets.

However, pKa is a notable exception among the fundamental physicochemical properties. Rather than thinking of pKa as an overall molecular property, it can be viewed as a localized property of each individual ionizable center, largely influenced by the type of ionizable group and its local chemical environment. Because of this, one can expect reasonably accurate predictions regardless of drug modality, provided the algorithm has sufficient data on the ionizable center. That said, incorporating new experimental data remains invaluable for fine-tuning predictions for specific classes of compounds.

Study Design

To support the points stated above, we evaluated the predictive performance of the ACD/pKa Classic algorithm using a database of PROTACs and their precursors with measured pKa values. These values were collected through collaboration with our partners as well as from public sources.

Approximately 4% of the collected compounds were excluded from the analysis due to suspicious experimental pKa values. For instance, the same compound showed a discrepancy of about 2 log units in pKa across two different sources. In one case, our predictor closely matched one of the reported experimental values, and some analogs were also well predicted. One compound with an unexpectedly high pKa was removed. This example highlights that, in some instances, predictions may be more accurate than experimental data.

After this data curation effort, the final dataset consisted of 253 PROTACs of different classes and their precursors, totaling 491 experimental pKa values. pKa calculations were performed using ACD/Labs Percepta v2023 and v2024. The older version did not include PROTAC data in its training, while the newer version incorporated this dataset into its model. Additionally, a data set of 49 PROTACs from Desantis et al.4, which had not been included in either of the models, was used for external validation purposes.

Results

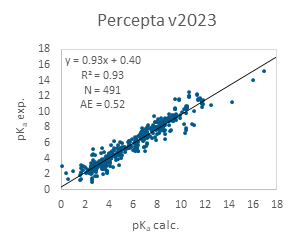

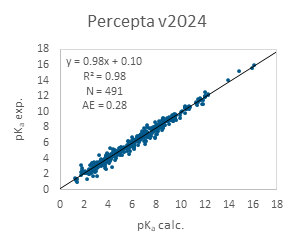

The pKa calculation results from both software versions for the entire PROTACs database are presented in Figure 1. As shown, Percepta v2023 already demonstrates strong performance, with only a few significant outliers where pKa is mispredicted by several log units. Incorporating PROTAC data into the model further improves accuracy, resulting in an almost perfect correlation in v2024.

Figure 1. Performance of ACD/pKa Classic algorithm on the entire PROTACs data set.

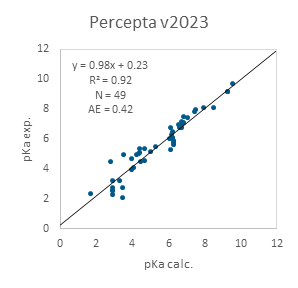

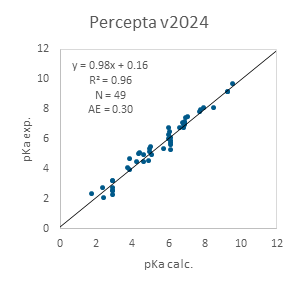

Figure 2 demonstrates external validation results obtained using the data from Desantis et al.⁴ In this case, the PROTAC molecules feature piperazine-containing linkers with additional ionizable groups within the linker itself, which can be significantly influenced by neighboring functional groups. Notably, this specific subset of PROTACs is also predicted with high accuracy.

Finally, Figure 3 presents examples showcasing the accuracy of pKa predictions using Percepta v2024 for a couple of specific molecules from Desantis et al.⁴

Figure 2. Performance of ACD/pKa Classic algorithm on a subset of PROTACs with piperazine-containing linkers from Desantis et al.4

|

|

||

| pKaexp = 2.74

pKaexp = 6.27 |

pKacalc = 2.90

pKacalc = 6.02 |

pKaexp = 4.69

pKaexp = 7.98 |

pKacalc = 3.85

pKacalc = 7.82 |

Figure 3. ACD/pKa Classic predictions in Percepta v2024 for piperazine nitrogen atoms in PROTACs from Desantis et al.4

Conclusion

Overall, the results of this evaluation study indicate that, in most cases, the ACD/pKa Classic algorithm provides accurate and reliable predictions, even for new therapeutic modalities belonging to the bRo5 chemical space, such as PROTACs. Additionally, the continuous incorporation of new experimental data further improves prediction accuracy and expands model coverage for novel compound classes and ionizable centers. Moreover, the performed data collection and curation effort highlights the utility of predictive tools for validation and verification of experimental data.

References

- Lipinski, C. A., Lombardo, F., Dominy, B. W., Feeney, P. J. (2001). Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Drug Deliv. Rev., 46(1-3), 3-26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0

- DeGoey, D. A., Chen, H. J., Cox, P. B., Wendt, M. D. (2018). Beyond the Rule of 5: Lessons Learned from AbbVie’s Drugs and Compound Collection. J Med. Chem., 61(7), 2636-2651. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00717

- Volak, L. P., Duevel, H. M., Humphreys, S., Nettleton, D., Phipps, C., Pike, A., Rynn, C., Scott-Stevens, P., Zhang, D., Zientek, M. (2023). Industry Perspective on the Pharmacokinetic and Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion Characterization of Heterobifunctional Protein Degraders. Drug Metab. Dispos., 51(7), 792-803. doi: 10.1124/dmd.122.001154

- Desantis, J., Mammoli, A., Eleuteri, M., Coletti, A., Croci, F., Macchiarulo, A., Goracci, L. (2022). PROTACs bearing piperazine-containing linkers: what effect on their protonation state? RSC Adv., 12(34). 21968–21977. doi: 10.1039/d2ra03761k